Reimagining Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr

“I know you will finish this film–if it takes you twenty years. I know you will… because you’ve sent me a clip of very fine stuff.” ~Werner Herzog

When I was an undergraduate, around 2008 or so, I bought the Criterion DVD of Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr. Although I was a Philosophy major, planning to pursue a career in academia, I was increasingly interested in filmmaking and had begun to take film production classes as electives. I had seen some of Dreyer’s other famous movies and found them to be among the best films I had ever seen. Fourteen years later, I still feel that way about way about La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Ordet. On watching Vampyr, however, I did not feel it was quite at the same level as these classics.

To be sure, I appreciated its formal and stylistic experimentation, as well as the early use of sound (the latter is no less unique than the soundtrack of Fritz Lang’s M, in my view). However, I did not feel that it succeeded as a horror film. This may have been because of its age, but as I read more about the film and learned about its lack of commercial success, I began to suspect that it was never very frightening. This seemed to be out of line with the filmmaker’s intentions, and I remember reading a late interview with Dreyer in which he downplayed the more radical stylistic aspects of the film. He instead talked about how, around the time he had decided to make Vampyr, he had noticed certain recurring horror genre tropes and wanted to try his hand at using them in a spooky film of his own.

With the presumptuousness of youth, I took it upon myself to see if I couldn’t make an update to Vampyr that would be more frightening. I would never have tried to improve upon any of his other masterpieces, which I considered perfect, but it seemed to me that Vampyr was more bold experimentation than flawless execution.

My Criterion set came with a small book that included Dreyer’s screenplay and the short-story, Carmilla, which was one of his primary sources for the film. I read both of them and then started writing a screenplay of my own, taking what I thought was best from each source and adding some ideas of my own. This was a slow process. I was a full-time student and had a job so I could only work on the script in my limited free time. I was also intimidated by Dreyer’s standing as a filmmaker and took my time so as to work carefully and create something that would do him justice.

It was also about this time that I saw David Lynch’s Inland Empire. I was rather blown away by it and the movie seemed to have been made in the same spirit as Vampyr. Both were produced in a low budget, independent manner, and both had elements of dream-like horror. Inland Empire really demonstrated the artistic possibilities of shooting on video, especially compared to many movies of that time which utilized video as a sort of low-budget, ersatz film stock. I began watching sections of both Vampyr and Inland Empire repeatedly, using the pause and rewind buttons to analyze them shot-by-shot. In conjunction with this exercise, I read David Bordwell’s book on the form and style of Dreyer’s films, which I found elucidating. I also found Jonathan Rosenbaum’s writing on Dreyer helpful, although I feared he would not approve of my project given his response to Lars von Trier’s adaptation of Dreyer’s screenplay for Medea.

As it turned out, Lars von Trier would also be a source of creative inspiration, particularly when Antichrist was released in 2009. I was very impressed with how this film externalized the psychological disturbances of the two lead characters, combining them with horror genre elements. I thought that Lars von Trier’s screenplay displayed a psychological depth that is often lacking in horror films, and that this was particularly well conveyed by Charlotte Gainsbourg in an unforgettable performance. I hoped my finished film would have a similar emotional impact, even if I was not aiming to be quite so gruesome or sensationalistic.

By Spring of 2010, I was about halfway through my loose adaptation of the source materials for Vampyr. It was at this time that I learned about Werner Herzog’s Rogue Film School. There was only a few weeks before the deadline, but if I hurried I could still apply. Werner himself would make admissions decisions, based largely on the quality of a submitted film clip. So, I took a short section from the beginning of my screenplay and brought on a talented young cinematographer who was well versed in film history. I then organized some friends who graciously helped us to shoot a short clip for my application. Although the budget was limited, I think I was most limited by time. I was unable to plan out the sort of complicated shots and blocking that are hallmarks of Dreyer’s film. Thus pressed, I put the following quote attributed to Werner Herzog on my call-sheet:

Coincidences always happen if you keep your mind open, while storyboards remain the instruments of cowards who do not trust in their own imagination and who are slaves of a matrix….

And with that attitude, we made the clip below without even a shot list. I submitted it to Werner, who watched it and admitted me to his film school. It was one of a handful of clips that he screened and discussed with the class. He asked me about the project and encouraged me with the words I have quoted at the top of this post. He told me I could take this opening and go anywhere with the rest of the film. Werner also compared what I was doing to his own re-imagining of Nosferatu. He understood the desire to engage with film history, and while he could be dismissive of some otherwise celebrated filmmakers, he affirmed Dreyer’s greatness.

As a visitor to my website, you will know that I have written a memoir about my experience of mental illness. Unfortunately, about a year after Werner encouraged me, I experienced the onset of psychosis. The next decade of my life would be lost. When I was living in a psychiatric facility in 2016, the irony that Dreyer had entered a psychiatric clinic shortly after the release of Vampyr was not lost on me. What the French film historian Maurice Drouzy calls les années noires de Dreyer followed and it would be ten years before Dreyer was able to make another film. Now that I am coming out of my own années noires, I fully intend to complete my re-imagining of Vampyr because, like Werner has said, “there is such a thing as half a loaf of bread, but there is no such thing as half a film.”

Below is the clip I sent to Werner and some images I have collected over the years as references for the visual aesthetic of my planned film, which could perhaps be more accurately described as a digital nightmare.

Inland Empire Still

The films of David Lynch, and Inland Empire in particular, were consulted and studied in detail. From the dark and smeary digital color palette to the non-linear plot elements, Inland Empire and Vampyr are digital nightmares for the 21st century

Rembrandt’s Painting

The young Rembrandt’s Pilgrims at Emmaus is representative of the approach to lighting and setting in Vampyr. This is in line with Carl Dreyer’s own stated preference for minimal mise en scène.

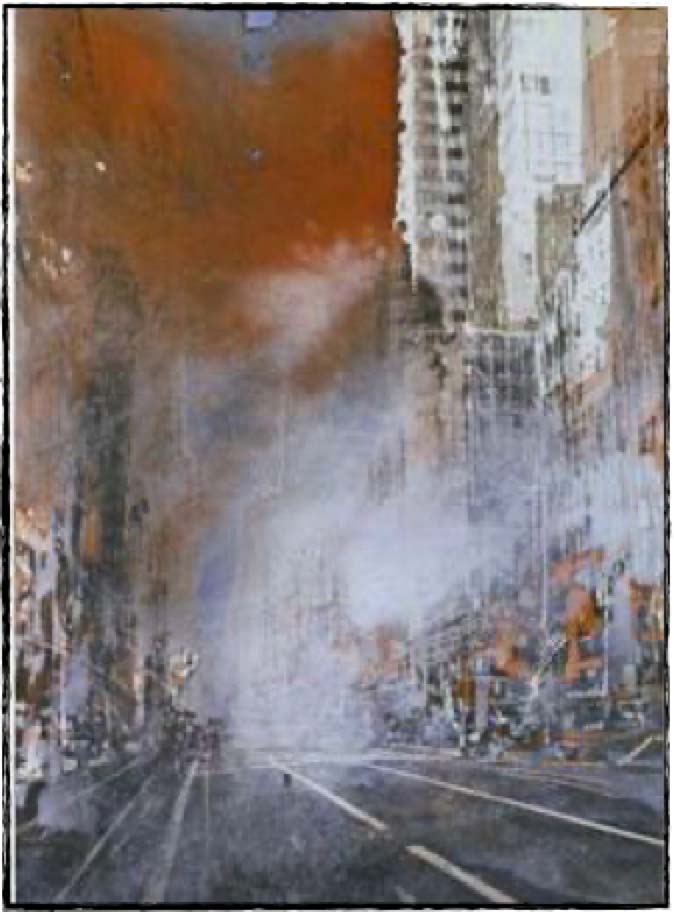

Gottfried Salzmann’s Cityscapes

While Dreyer’s Vampyr is set in the countryside, I decided early on to set my version in an urban environment. In 2012, I saw Gottfried Salzmann’s paintings at Franklin Bowles Gallery in San Francisco and was immediately struck by how they evoked the sense of urban dread that I want to convey with Vampyr’s exteriors.

Suzanne Caporael

One of the most masterful sequences of Dreyer’s film is the procession of shadows, which represent malevolent spirits of some sort. Still unsure of how to update this sequence, I came across Ms. Caporael’s work at the Chazen Museum of Art in Madison, WI. I made a note of this painting and a few others as references for how I might depict the shadowy creatures in my film.

Portrait of Misia Sert

When I saw this portrait of Misia Sert by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, I was reminded of the section of Dreyer’s film that takes place in the manor. The painting has a dream-like quality that I would like to emulate in the corresponding section of my own film.